My sister was in town for the holidays, which meant she was going to visit our father. She had not seen my father since he was hospitalized after his stroke in March.

She wanted someone to go with her. I told her my brothers, who were staying at my mom’s house for Christmas, would be happy to take her.

But she said she wanted someone with experience. A “veteran,” she said. And that veteran was me.

I knew and she knew it would be an emotional visit with my father.

Ours is a complicated relationship, and as he learns to swallow, talk and move his appendages all over again, his triumphs and difficulties seem to carry even more meaning.

We arrived at the nursing facility, and she walked with me from the back of the facility toward his room. His room is near the front of the facility, and his bed is near a window that faces a main street. It’s not a bad view. The passing cars can serve as a distraction and have a rhythm to their flow. There are sufficient trees to add some color and softness to the mix of concrete and asphalt.

I loudly announced my presence, but he seems to hear or sense when someone walks in the room because he had already turned his head to look in my direction as my words made their way out of my mouth.

He saw that my sister was somewhat behind me as I told him he had another guest.

I turn to look at her and move aside so she can have access to his bedside.

My father began to sob as she approached him.

She asked him how he was doing, and I heard her voice crack before I saw the tears well up in her eyes. She hugged him because my sister is a hugger.

She asked him how he was doing, and I heard her voice crack before I saw the tears well up in her eyes. She hugged him because my sister is a hugger.

There was silence.

I wondered what he would say to her if he could speak. Or if he would say anything at all. We were never good at talking about the obvious. And when you add hurt and a complicated past, it gets…complicated.

My sister wiped her tears away, and I told my father it was OK.

I transitioned into my usual routine of sharing the latest family news, current events, etc.

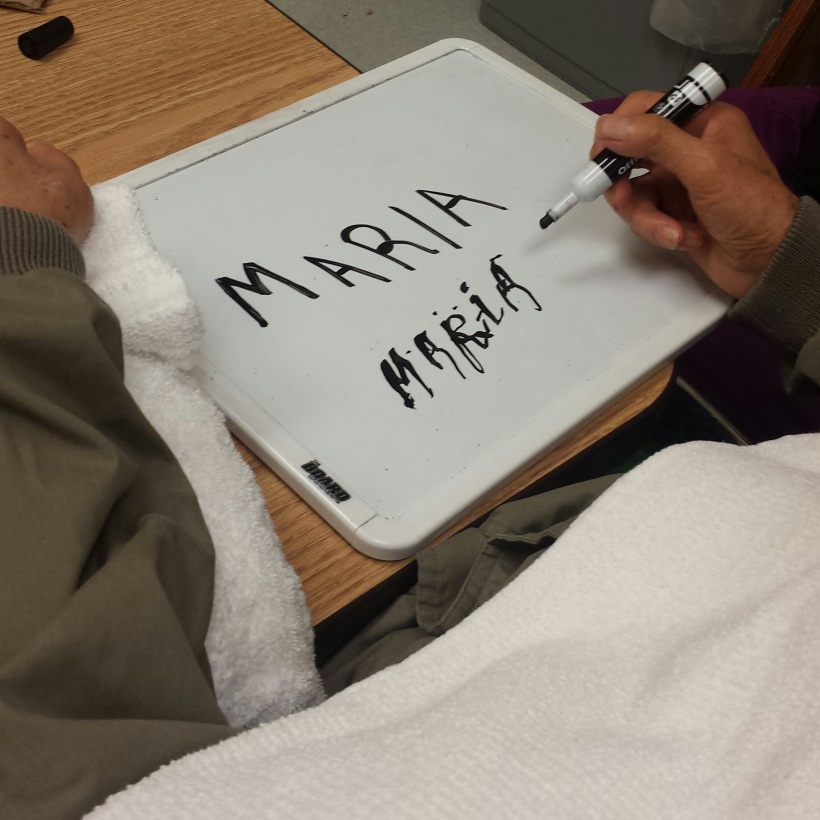

We practiced writing on his whiteboard, but it looked like he was either trying to write his full name in cursive or he was attempting to write Chinese characters. It’s possible he was too emotional to write and could not concentrate. So we practiced just writing the letter “F”, for Frank.

My sister stepped out of the room for a few minutes.

When she returned, my father and I were still working with the board.

I switched gears and asked if he’d like to see some photos.

He nodded, and we started going through the photos on my phone.

I checked the time and my sister and I told him we had to make a mad dash across town to LAX so she could catch a flight home.

Since their emotional greeting he had not looked at her, and the mix of joy, embarrassment and possibly guilt still hung in the air.

My sister asked me if I noticed, and of course I noticed, but I was not surprised.

Since their emotional greeting he had not looked at her, and the mix of joy, embarassment and possibly guilt still hung in the air… Even before his stroke the words to apologize and explain often eluded him. And now, sitting in a bed, completely dependant on someone else, without the ability to say a word, my once fiercely independent, loud and commanding father has no control of his world.

Even before his stroke the words to apologize and explain often eluded him. And now, sitting in a bed, completely dependant on someone else, without the ability to say a word, my once fiercely independent, loud and commanding father has no control of his world.

He has a Chinese calendar in his room now, and I showed him on the calendar that he had a week off before he begins his work with the USC therapists again.

The occupational therapist worked with him on straightening and extending his fingers, and she soon presented him with an opportunity to practice writing.

He immediately began to write his name when the therapist handed him the marker.

The letters appeared shaky, but it was clear enough to make out his name.

She asked if he could write my name, and then she wrote my name on the dry erase board and asked him if he could trace over it.

He looked at the board, studied the words and then wrote my name.

I was sitting across the table from my father and the therapist, fiddling with my phone, when I heard the therapist’s voice rise in delight. She congratulated him on writing my name so clearly. I looked up. I too was delighted. I walked over and snapped a quick photo and congratulated him.

My father started to shake and his face became red. His emotional reaction to writing my name made me emotional as well.

Especially because the word was written so clearly.

He continues to make progress with his ability to swallow, and it is not uncommon for him to be able to swallow after he coughs. It is also a littler easier for him to swallow, and he is now swallowing without the assistance of the VitalStim therapy (electrical stimulation for his throat muscles).

The speech therapist also began having him practice talking – mouthing responses in addition to nodding or shaking his head.

I often wonder if he wants to talk. Perhaps it’s easier for him not to since it allows him to continue avoiding the past. Perhaps he does not want to discuss what is happening to his body and his mind.

We came to an agreement that once he began eating, I would take him out to dumplings. I asked him one day if he missed eating and the taste of different foods. If he missed Chinese food. He laughed. Which I think means yes… I have not mustered the courage to ask if we wants to talk.

We came to an agreement that once he began eating, I would take him out for dumplings. I asked him one day if he missed eating and the taste of different foods. If he missed Chinese food. He laughed. Which I think means yes.

I have not mustered the courage to ask if he wants to talk.

A few times in therapy we leaned in to hear him utter a very low, hoarse response.

Of greater importance is the opening and moving of the mouth, tongue and all the related muscles, the therapist said. Sounds, of course, are great, but she wants him to engage more.

Back at the skilled nursing facility, I practiced what he had done in speech therapy, encouraging my father to “talk” and mouth his responses.

Before leaving, I mentioned when our next appointment was, and asked if that was OK, or “good” with him, in Chinese.

“Hao?” I said.

He nodded and opened his mouth.

“Hao,” he responded, in a raspy, Darth Vader-like voice.

“I could hear that!” I said. “That’s good – hun hao (very good).”

He began to shake and cry.

These are small steps, but steps nonetheless, I told him.

“Hun hao,” I repeated, with tears in my eyes.

Very good indeed.

Such a lovely writer you are Maria. Hun hao.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thank you and so nice to hear from you 🙂

LikeLike

Beautifully and movingly written! You are doing a terrific job caring for your father.

Rose

Sent from my iPad

>

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thank you and thank you! I had a few good teachers 😉

LikeLike