As the anniversary of my birth quickly approaches, along with the end of this year, I find that I have much to write about. The most recent posts here are about my father’s path to recovery after a stroke.

My father did not regain his ability to speak or walk, and in the last few months of his life, he suffered greatly. For a very long time – six years – I could not write about what that felt like and that he was no longer here in this world with me. That I could not talk to him. And I found that what I wanted most after his stroke, was to talk to him. But the stroke left him paralyzed on one side of his body, he could not speak, and was eating from a feeding tube. I wanted to talk to him about the small things, like the weird person on the train, what I ate, or what happened at work. But also about more important stuff. About his life in L.A. His journey to the U.S. from Shanghai and Hong Kong and what his life was like before me and our family existed.

I have been working and living in his native Shanghai since January of this year and celebrated his birthday and marked the anniversary of his passing here. There is a large park and a small restaurant with the most amazing crab xiao long bao (XLB), which are soup dumplings, near the street where his family’s home once stood. It is within walking distance from the hotel our family stayed at during our 1987 visit. I’ve been in the area multiple times now, and sitting on a park bench, with a view of the hotel and other landmarks near the popular Nanjing Road East pedestrian street makes me feel like I’m home. It makes me smile and shed a few tears. I would love to have a conversation with him about my time in his hometown so far. The beauty, the strangeness, the difficulties, and how much I’ve enjoyed (most of) my experience here. All of this has been on my mind, and I finally decided that this was the time to write about it. I also wanted to share a post that I wrote one year after he died. At the time, I was unable to make it public.

The hotel we stayed at with my father in 1987, during our family trip to China. It’s walking distance from where his family’s home used to be. Photo taken in April 2023.

Saying Goodbye

(Written in 2018)

My father died last year on Labor Day. It was a Monday. And it was quiet. The only noises in the hospital room were the beeping of the machines he was hooked up to. The streets were empty on the ride home because of the holiday. The morning commuters whose cars normally clog these streets were nowhere to be seen.

His heart had stopped beating on a Sunday in September, and he was rushed to the hospital. There I watched the slowly ticking clock as his heart rate continued to plummet. The doctor told us he would not make it through the night. There was nothing more to do for him. His body had finally had it. After a massive stroke in March 2015, physical, occupational, and speech therapy, as well as acupuncture and acupressure sessions, rides back and forth to each, a bout with shingles, countless appointments with specialists, and two hospitalizations in the last two months of his life, my father could fight no more.

The Thursday before he died, I dreamt of him.

In the dream, I was in a hospital waiting room. My youngest brother had spoken to the doctor and was told my father had no brain activity. As the dream continued, I watched myself converse with my brother and walk over to my father’s room. I stood by his bed and I saw my father’s spirit rise from his body. I was not afraid. I just watched. Sound did not come out of his mouth, but he was speaking to me. He apologized. He said he could not hold on any longer. I wanted to cry, but I managed to respond. I said that he had nothing to apologize for. That I wished things had gone differently, but I knew that it had been an extremely difficult few months for him and his body. I said I understood and it was OK. He thanked me for helping him. I don’t remember the rest of the dream. But I was suddenly awake. Breathing hard and crying. Afraid and despondent, I did not want to acknowledge what I seemed to already know.

It has taken me some time to muster the courage to put something on paper and send this out in the world. I initially could not describe the loss and the sudden emptiness and strangeness that come when a person leaves your life. It did not matter that he had been so ill the last few months; that the stroke had robbed him of his ability to walk, talk, and live independently. We had bonded during his treatment sessions and doctor checkups. If anything, the most recent hospitalizations came in stark contrast to the previous months when he was doing so well — writing in Mandarin, joking with his therapists, and seemingly ready to start the long process of being able to swallow consistently. He answered affirmatively when his occupational therapist asked him in Mandarin if he wanted to eat again.

But he is gone. Despite all my efforts, all my time, and all my pushing and prodding of nurses and administrators at the skilled nursing facility, he could not recover after his July hospitalization. By August it was clear to me that I should prepare for the worst. While my father could not communicate verbally, I was closer to him in those last two years of his life than I had ever been. Perhaps because there were no words to wound each other with, we were able to share in each other’s lives. Accompanying him to his therapy and acupuncture sessions are not moments that I will ever forget. It was amazing to watch him will his body to do things it could once not do. And it was great to be a part of the relationships he was establishing with his therapists and acupuncturists.

The following is what I said about my father at his 2017 service:

My Father

My father’s most recent stroke in 2015 rendered him speechless, paralyzed the left side of his body, and robbed him of his ability to walk and swallow.

As his caretaker for the last two years, I accompanied him to his appointments and spoke on his behalf. Ironically, this once bombastic and fiercely independent man was now dependent on those around him. We were on speaking terms before his stroke, but we still fought. But in watching and supporting his progress in occupational, physical, and speech therapy, and during acupuncture treatments, something changed between us.

Now, as I witnessed his efforts to command his body to move or force sound from his mouth, the past seemed further and further away. The hurt, the anger, and the annoyance became less and less important. What mattered now was helping this battered and imperfect man before me.

When he was able to say “hao”, which means good in Mandarin, in a low raspy voice after a speech therapy appointment, we both became emotional.

When he moved his paralyzed left arm, I congratulated him.

When Michael (one of my brothers) and I were hitting a balloon back and forth with him, my father laughed with us when I blamed my brother for the break in our rhythm.

We are all imperfect. We will continue to stumble. But to hold on to anger and resentment is the greater failure. To share in someone’s life, no matter how limited the time, is a great gift. I regret that I did not have more time. But I will remain forever grateful for the past two years and the opportunities to spend time with a man who has continued to shape my spirit.

Zàijiàn (see you again) Yun-Nie.

My father’s Hong Kong passport photo.

Two Words Two Years After a Stroke

And since 2015, after his most recent stroke robbed him of his ablity to swallow, stripped him of his speech, and rendered the left side of his body useless, he has said two words to me.

It is March 22, 2017.

Today my father almost cried. Again.

If you knew him, you would know this rarely happens. I did not see him cry at his mother’s funeral in Shanghai — despite that being the first time he had seen her since he left China in the ’60s. Nor did he cry or show any emotion when he was handed divorce papers.

I am not sure I can recall ever seeing him cry.

Raise his voice and yell — that was much more common.

And since 2015, after his most recent stroke robbed him of his ability to swallow, stripped him of his speech, and rendered the left side of his body useless, he has said two words to me.

Last year, in January, after practicing mouthing words with his speech therapist and being able to get out low, raspy vowel sounds, my father and I practiced some more upon our return to the skilled nursing facility. Before leaving, I reviewed his next appointment with him, and asked if that was OK, or “good” with him, in Chinese.

“Hao?” I said.

He nodded and opened his mouth.

In a raspy voice, he answered: “Hao.”

I was so excited I shouted, “I could heart that!”

My father began to shake and cry.

Since his stroke in March 2015, he is a different man. I have seen him sob perhaps a dozen times. Sometimes the tears he shed were from joy. Other times, they were from frustration.

Today, after acupuncture in Torrance, where the acupuncturist uses a unique set of tools that help his brain and body reconnect with each other, in addition to needles, my father began to make grunting noises. Almost like he was testing out his vocal cords. This had happened before but he did not attempt any words.

When he did this today, I asked if he could say “ah”.

He did.

I called to the acupuncturist who was at the front of the office with the receptionist and shared the news.

Again I asked if he could say “ah.”

He did.

The acupuncturist and I both told him what a great step that was to be able to utter a word.

And then I asked him if he could say “hao.”

“Hao,” he answered, in a slightly lower voice.

I told him that he was continuing to make progress, and that his efforts were paying off.

His face began to contort, and I thought he might cry. I thought I might cry. He has not spoken in two years and has made very little vocal sounds, with the exception of the grunt that usually precedes a cough.

Perhaps it is karmic that the tool he often used to inflict pain would be taken from him and that he would not have the ability to speak for himself at a time when he greatly needs it.

I did not think I would miss talking to him — exchanging words with him — since we fought so often. But now I find I want him to talk and answer me, and I often wonder how his voice will sound if he does regain the ability to speak.

In dreams we have often walked and talked together, usually while going somewhere for a meal. I once dreamt he was talking with a doctor and explaining how he was feeling before he gained the ability to speak, and it was only then in the dream that I realized he was talking. Maybe it means nothing. Maybe we are destined to find other ways to communicate. But today’s experience, on the day before the second anniversary of his stroke, definitely felt like something.

In the photo above, cotton balls and the packages that hold acupuncture needles are seen after a recent visit to one of my father’s acupuncturists.

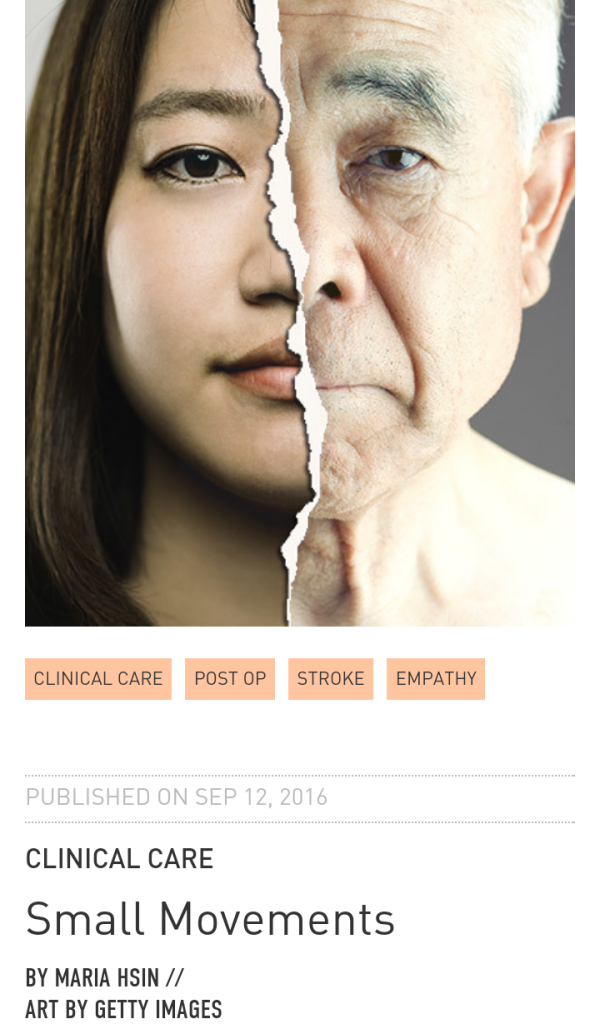

Small Movements

The subway and then the bus took me east to the hospital, through the neighborhoods of Los Angeles, to say what I know we should have said to each other years ago. Decades ago.

BY MARIA HSIN //

ART BY GETTY IMAGES

The subway and then the bus took me east to the hospital, through the neighborhoods of Los Angeles, to say what I know we should have said to each other years ago. Decades ago. He wouldn’t respond—he couldn’t—but at least I would have said it out loud.

“Stay With Me” played on my Pandora station. Fitting. I was headed there to plead that he stay. That he open his eyes and understand me.

My father and I had a long, rocky relationship, and in the past year he had suffered a major stroke. It rendered him speechless and unable to swallow or move the left side of his body. Because of the abnormal way his heart pumps blood—a separate condition—the doctors didn’t think that things were going to get better. The latest complication was pneumonia. If I was going to say anything, now was the time.

He was awake when I entered the room. I hadn’t seen him open his eyes since he was transferred back to the hospital with a fever of 101 a few days ago. Now his gaze was locked on something.

I cautiously stepped closer to him. When I spoke, he looked up at me.

I said hello in Mandarin. I held his hand. I wanted to see if he would squeeze it back when I asked him to. His strength had diminished. We went through our usual routine—I asked him to move his fingers, feet and toes—and the pistons began to fire, as the machine that was his nervous system seemed to warm up.

With puffy eyes and a red nose, I began my speech. I apologized, and said I knew we hadn’t gotten along for many years, and that there was a lot we had not said to each other. I started to cry and his face became red, and he shook. He was crying too. I felt bad, and then realized he had understood me, that he was acknowledging our difficult past. That it had hurt him too. I stopped crying and I told him it was okay. It was time to focus on his hands and his movement right now.

I remember the screaming and the crashing of plates from my childhood, all too many nights. I longed for my mother to leave him. I remember his betrayal and his verbal abuse. After the divorce, we erased all physical traces of him from the house. But his daring, his cooking and what I knew of his culture—they lingered in my psyche and in my heart.

Of course I had regrets about the years that followed. I could have spent more time with him, I could have done a better job documenting his journey from Hong Kong and Shanghai to America. I never learned enough of his native Mandarin to converse with him in his language.

Other attempts to confront the past, and all the hurt, had failed. As we shook, after my speech, I wondered if his tears and mine might be some way forward.

It has been a year since then, a year of watching my once commanding and independent father struggle, helpless, in his body’s rebellion. I have learned to see that he is just a man, flawed and broken, in many more ways than before. I see that I have an opportunity to talk to him, to share my life with him. One day, he may talk back. I now speak for him at his therapy appointments. I celebrate his progress, including the day he was able to say hao, or “good,” in Mandarin.

Some people have asked why I would do this. The answer, I now realize, is simple. Because I see that he has not given up. He is certainly not the man he was before, and he may not be able to do the things he did before—including cook or walk. Perhaps it is this transformation into someone else, someone we both are discovering, that will finally allow us both to be free of the past.

“Small Movements” was published in Proto magazine.

When Therapy Runs Out

We have almost exhausted my father’s allotment of therapy for his stroke. Will supplemental insurance make a difference? For now he is seeing an acpuncturist twice a week.

Sometimes it feels like we are going in circles.

In order to get better after his most recent stroke, my father needed therapy. He could only tolerate so much therapy when we started. And then when he could tolerate more, and was starting to make progress, we had to decide how much therapy and which therapy to keep.

As you may have guessed, Medicare will only provide a certain amount of money for therapy. To complicate matters, speech and physical therapy funds come from the same bucket. And speech and physical therapy are what he needed the most.

We have already seen a difference in how easily he is able to sit up once he is moved from a wheelchair to a bed at therapy. When he was attending weekly, not surprisingly, it was easier for him.

If he needs therapy to get better, goes to therapy, then tolerates more therapy and makes progress, but then has to stop, how will he get better?

If he needs therapy to get better, goes to therapy, then tolerates more therapy and makes progress, but then has to stop, how will he get better?

I have looked into supplemental Medicare plans, but that will not help his current situation and get him addditional therapy.

A family member might be able to add him to his insurance, but that might not happen until next year. Which means my father, who is still making an effort to get better, will go half a year without therapy.

I asked what it costs to pay out of pocket for therapy, and it is not cheap.

The good news is he makes progress with mental stimulation exercises, particularly math and multiplication tables. He is now up to the “6” times tables and one of the activities persons at the skilled nursing facilty is supposed to review them with him (in addition to being mentally sitmulating, it is something he enjoys). For some reason his mind remembers addition and subtraction easily, but multiplication has become a challenge.

He continues to move his left arm slightly during occupational therapy exercises. The left side of his body was paralyzed whe he had his stroke last March.

And he recenlty moved his left thumb.

While these are all minor improvements, they are still cause for celebrating. I remind him that each small improvement will lead to more, and the more he is able to move, the easier it will become.

Acupuncture is going well, and his traditional Chinese acpuncturist immediately recommended herbs that have helped with his circulation. His skin color looks healthier, he is more alert and he is holding his head up better.

He is now tolerating twice-a-week appointments.

It is slightly easier for him to close his mouth, which is important for swallowing. Swallowing is still difficult, but when he closes his mouth and then “chews”, it is a little easier for him to swallow. But oftentimes he must be prompted verbally to do so, and sometimes verbally as well as physically (tactile sensation on his chin and tongue are usually the triggers to get him to swallow).

It is slightly easier for him to close his mouth, which is important for swallowing. Swallowing is still difficult, but when he closes his mouth and then “chews”, it is a little easier for him to swallow. But he must be prompted verbally to do so, and sometimes physically and verbally (tactile sensation on his chin and tongue are usually the triggers to get him to swallow).

We have our light moments.

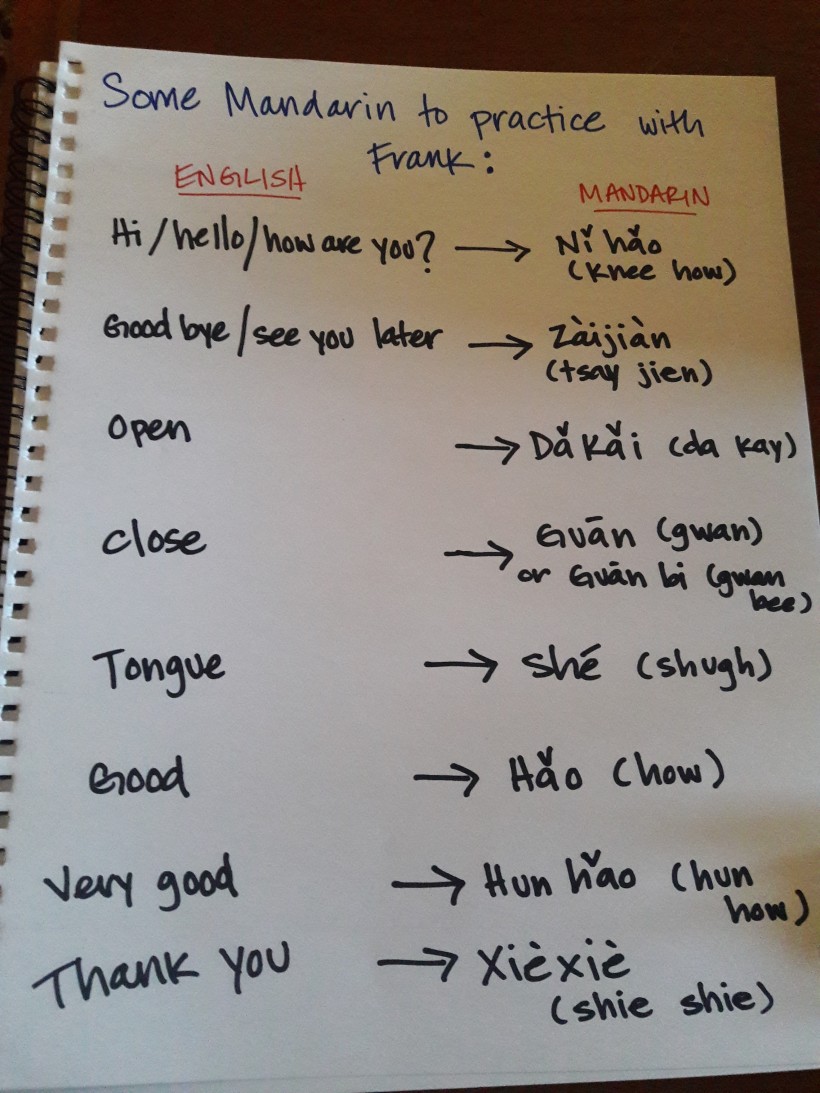

My significant other, who is fluent in Mandarin, taught me to say, “I speak a little Chinese.”

Like an eager tourist, I tried out my Mandarin on a native speaker. My father listened, and then he started to laugh. I asked if my Chinese was OK — I wasn’t sure if he knew it was Chinese — and he nodded. Then I asked him to tell me if it was good (thumbs up), so-so (rotating hand side to side), or bad (thumbs down).

He graciously said it was so-so.

It reminded me of the time I called him several years ago to tell him I was taking a Mandarin class. He said to tell him something in Mandarin. I did. But he had trouble understanding me, so I repeated it a few times. Then he said to just tell him in English.

His acupuncturist helps me translate and speaks a few words of Spanish to me sometimes because she knows I am part Mexican. A few times she has teased him, in Mandarin, for not teaching me to speak his language.

And at a recent acupuncture visit he moved his left arm. He lifted it when I asked. It was a very natural movement, immediate and deliberate. For a second or two I forgot the left arm has not moved since the stroke last year. Then the realization hit me.

“Hun hao (very good),” I exclaimed. “You raised your arm, that’s great!”

And at a recent acupuncture visit he moved his left arm. He lifted it when I asked. It was a very natural movement, immediate and deliberate. For a second or two I forgot the left arm has not moved since the stroke last year. Then the realization hit me.

He could only do it once, and knows whether he can or cannot move it. It fascinates me to hear his occupational therapist ask him in Mandarin if he can move his arm or if he can move it again after an exercise. He answers honestly, and immediately.

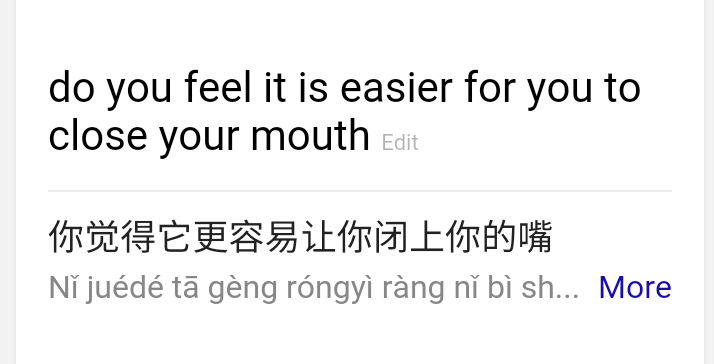

Our trips to USC Keck Medical Center for outpatient rehab have become less frequent for the moment, which is why I increased his acupuncture treatments. It seems to me it is a little easier for him to close his mouth, and I wanted to get his feedback. So I asked.

Google translated for me and when I played the question for him in Mandarin, he listened. Then he nodded.

This might sound like a simple question. Or an odd question. But for a person recovering from a massive stroke — who cannot eat and has difficulty swallowing, closing his mouth and being able to keep it closed, and command the muscles to obey and move and swallow — the ability to answer that question affirmatively is quite a feat.

Practice makes it easier. And having someone help him practice when he is not at USC for therapy, or with his acupuncturist or with me, is a challenge. We will soon see if with some additional training the staff at the skilled nursing facillity will be up to the challenge of helping him perform some basic exercises to trigger a swallow.

He is scheduled for a visit with my acupuncturist later in July. Some readers of this blog may recall I had a complicated ankle injury that involved damaged nerves, a sprain and a minor fracture. I had difficulty moving my toes, could not move my foot to the left and was on crutches for half the year.

My official diagnosis was Chronic Regional Pain Syndrome (CRPS) which in severe cases make life extremely painful and dibilitating. Not to say that my time on crutches was a pleasure. I rarely take medication, I prefer the natural route. But the pain was so severe at times I had to take pain meds, and then suffered the side effects.

The CRPS was causing false pain messages to be sent to my brain and with physical therapy and acupuncture, I was eventually able to walk and run again. My acupuncturist essentially “rewired” me so that messages would no longer travel on the paths that were sending the pain message to my brain.

I am curious how this will help my father after a stroke. I know that it will, that has already been made clear. But with her particular bag of tricks, things will get very interesting.

Father’s Day Is Sometimes Complicated

The holiday has caused such confusion and questioning that for a long time it was easier to ignore it and its significance.

I never knew how to feel about Father’s Day.

As a little girl, I probably was obligated to make a card for my father in school. As I grew older and sparred with him verbally, I chose not to celebrate Father’s Day. My father was not the “World’s Best Dad” or “No.1 Dad” — I knew this at a young age. Then as adult, I eventually understood that he knew he had made mistakes as a parent and father, and I had started to meet him for lunch or dinner and share my life with him.

My father was not the “World’s Best Dad” or “No.1 Dad” — I knew this at a young age.

Last year he had another stroke, and I became his caretaker.

And then Sunday was Father’s Day.

It had occurred to me to get him a card, or enlarge a photo that he indicated he liked, or do something to mark the occasion. After all, he is still alive, aware of his surroundings and continues to make progress during therapy.

But making the journey from Orange County to L.A. for his appointments (three or four a week, depending on his therapists’ and acupuncturist’s schedules) is not easy, and the physical and emotional strain is high.

I accompanied him to acupuncture Saturday, and the coward in me thought it might be best to not acknowledge the holiday. If I did, I knew I would start crying, and then I would surely upset him. While I have told him that we both made mistakes and that I would prefer to have him in my life, there are so many little things we have not said.

As it turned out, I was in the area after all on Sunday.

My compromise with myself was to stop in on him at the skilled nursing facility, say hello, ask him how he was doing and let him know I’d be back in two days to accompany him to speech therapy. I told him my visit would be brief because I was on my scooter and wanted to get home before traffic became too heavy and the day became night.

He raised his arm and moved his hand in a way to indicate he felt so-so on this day, and after a few more questions I said goodbye.

The stroke has changed him, especially physically, but even before that, he had been humbled by other strokes and age. He was no longer the commanding and frightening authority figure. He became a man who waned to communicate with his children, although he lacked the tools to do so.

The stroke has changed him, especially physically, but even before that, he had been humbled by other strokes and age. He was no longer the commanding and frightening authority figure. He became a man who wanted to communicate with his children, although he lacked the tools to do so.

I am certain I am not the only one who feels ambivalence or confusion on this holiday. Even the president of the United States has complicated feelings towards a father he hardly knew. It brought me some comfort to read the article about the trove of letters written by Barack Obama, Sr., preserved, sitting in a box, awaiting the day his son is ready to read them.

Connecting with Connect Four

It was Sunday, and I thought I’d pay my father a visit at the skilled nursing facility. A caretaker who accompanied him to acupuncture the day before said his left arm was very active and that the acupuncturist was working to awaken his throat muscles and improve his ability to swallow.

I was curious if I’d notice a difference in his appearance or demeanor after my 10-day trip to Chicago.

He was awake when I came in, not quite laying down and leaning to his left. He didn’t look very comfortable. Despite knowing how to call for the nurse, he does not use his call button. I snagged two nurses from the hallway and asked that they kindly sit him up.

His most recent stroke was in March 2015, and he has been living at a skilled nursing facility in the Highland Park neighborhood of Los Angeles (northeast of downtown) since last May.

The stroke left him paralyzed on the left side of his body and he cannot yet speak. A few times he’s managed to say a word loud enough for me to hear. He swallows more than before, but it is still not enough and he remains at risk for pneumonia if his saliva goes to his lungs.

It’s not all bad: my father recently moved his left arm, and indicated he’d like to walk. He is aware he must strengthen his upper body, and has been an active participant in physical and occupational therapy since we confirmed he was indeed moving his left arm at will. At a recent occupational therapy visit he sat with zero to minimal support for several minutes. When asked, he nodded that he wanted to try and stand. Assisted, of course.

We reviewed my Chicago photos, which included food, and various buildings around the city that were part of the “L” train tour I created (I have a fascination with architecture and building design) and the gorgeous views from my boyfriend’s family’s cottage near a lake in Hastings, Michigan. The photos also included the murals that dot the area around Chicago’s Columbia College and Wabash Arts Corridor.

I noticed he was very alert and he seemed curious about what I would show him. He was happy to view the photos on my tablet and when we were done, he watched carefully as I closed the tablet and set it aside.

To transition to physical activity, I asked about his right hand and how much he is able to open it. I then asked about his arm, and more questions led to a mini physical therapy session, where he had to touch the top of his head or his left shoulder. A few more minutes of this continued with head, mouth and leg exercises. I reminded him how important it is for him to move, even while he is in bed.

I asked if he wanted to play Connect Four. He did not say no, so I walked over to the closet and pulled out the box. I showed it to him and asked if he remembered playing with his therapist at USC Keck Medical Center. He quickly nodded.

For those of you born after 1974 when the game was first sold, small, round, plastic discs are inserted into a frame and the first person with four discs in a row, either horizontally, vertically or diagonally, wins the game. Think Tic-Tac-Toe, but instead of an “X” or “O”, each person picks a round, colored disc.

Our game features yellow and red discs.

While he cannot speak yet, my father is completely aware of what is going on. His addition and subtraction skills are still intact, although multiplication is giving him problems and he usually has homework that involves reviewing multiplication tables (he’s on the 4’s at the moment).

He also still likes to read. Like my grandfather who had his own printing company in China, my father had his own printing business. He greatly enjoyed or was greatly intrigued by a recent story about meat turning fluorescent blue in China. It was under investigation the last time I checked, but government officials warned people not to eat any blue meat.

I set up the game, and on this day I was red, he was yellow.

I knew I had to pay attention during our game, and I had no intention of letting him win. Now, before you start to feel that I am a cold-hearted daughter, you should keep reading. Yes, I blocked his moves a few times and to my surprise, he got a BIG kick out of blocking me.

I knew I had to pay attention during our game, and I had no intention of letting him win. Now, before you start to feel that I am a cold-hearted daughter, you should keep reading.

You can see from the photo below that I was making my way across diagonally, and his yellow disc stopped me from winning the game.

“Hey, you just blocked me!” I said in surprise. He started laughing and I started laughing. We laughed for a while. Sometimes his laughter is silent, and I only see his mouth open and his body shake. But on this day, I could actually hear noise as he laughed.

We carried on with our game. At one point I asked if he wanted to continue playing because it didn’t seem anyone was going to win.

He ignored me, so we continued to play.

I thought I might have some luck on the right side of the board, and wasn’t really paying attention to what he was doing.

On his next move, I saw he was more eager than usual to get a disc in to the frame.

I saw where he might be placing it.

“Where are you putting that piece?” I asked, hoping he was not doing what I thought he was doing.

He focused on what he was doing, ignoring me again, and finally dropped the disc in.

I didn’t say anything.

Then he raised his arm again, and motioned to the four yellow discs that appeared horizontally on the frame.

In case I wasn’t paying attention, he was letting me know the obvious: he just won the game.

Then he raised his arm again, and motioned to the four yellow discs that appeared horizontally on the frame. In case I wasn’t paying attention, he was letting me know the obvious: he just won the game.

One Year After a Stroke: What Now?

I don’t remember who was on the other end of the call, but I do remember the words: my father had had another stroke.

My father lay in the emergency room while we waited on the results of an MRI to tell us the extent of the damage and to confirm he did indeed have a stroke. He had already lost control of the left side of his body and could not speak, but the grip in his right hand was strong.

This was a year ago.

A year of riding a rollercoaster that has felt like it was stuttering, coming off the tracks or like it would never stop.

A year of asking what else could be done, what would happen next and why he wasn’t swallowing, talking or moving the left side of his body.

A year of willing the incompetent and careless to give me what I needed to make my father’s life in a skilled nursing facility a little better.

In the process, I have been labeled “the daughter,” code for a word associated with females who are perceived to push too much and demand too much. Silly me for daring to ask that he be clean, groomed and spoken to like a person. That he be encouraged to get better. That he make it to his therapy appointments on time so that he can get better.

A year of willing the incompetent and careless to give me what I needed to make my father’s life in a skilled nursing facility a little better.

In the process, I have been labeled “the daughter,” code for a word associated with females who are perceived to push too much and demand too much.

There have been many conversations with doctors who claimed there was no hope — that he would not make it out of the hospital after such a massive stroke. That he would not wake from a coma after the stroke.

Most emphasized that the one-year point was the standard for recovery. When pressed about whether no one ever recovered after a year or even the possibility of recovery after a year, they would say it was possible to recover after a year, but the odds were not great.

Indeed, last month when my father nodded that yes, he had pain in his left arm and leg, we visited a neurologist in Glendale.

He essentially said, “If it’s been a year, that’s it. There’s not much more that will change.”

I was surprised by his assessment, given that this was the first time he had seen my father, that he knew nothing of the progress, although small, that my father makes each week in therapy, and because our time with him was shorter than the drive to his office. It was a roughly 20-minute drive, in the L.A. rain.

The neurologist noted my father’s inability to move the left side of his body, his inability to speak, and that he was using a wheelchair. I thought to myself, “Well, at least the doctor isn’t blind.”

It was also nearing the end of the work day, and I wondered if the doctor was eager to get us set up with X-rays, and out the door.

In short, the neurologist said, there is no sure way to tell what is causing the pain because my father cannot fully explain what he is experiencing. It is likely the pain he feels is caused by the nerves and muscles that are tightening because they are not moving the way they used to.

To help with the pain, we are going to go the natural route, and stick to acupuncture. It has helped him relax, given hime more energy and made moving and simple tasks like closing his mouth much easier.

So if the neurologist we saw was unable to tell me what else we can look to to help my father become more independent, who can?

And is stroke recovery even possible after six months to a year? The common thinking on this topic is that the most improvement happens during this time. But then what do people affected by a stroke do? What should they expect?

The short answer is recovery is possible. And happens.

A 2008 TED Talk by Jill Taylor, who also wrote “My Stroke of Insight”, revealed that the 37-year-old, Harvard-trained brain scientist was fully aware of how she was losing her ability to complete a simple task because she was having a stroke.

She describes how the process of moving to that thing that allows you to speak with someone else was now a monumental undertaking. Dialing a phone number was accomplished by matching the “symbols” or phone number, on a business card to those on the key pad of the phone.

Her stroke took place on a December morning in 1996.

It took the neuroanatomist eight years to fully recover.

There are clinical trials on stroke recovery using stem cells, and I recently read an article about a program at the University of Cincinnati that focuses on long-term stroke recovery.

The program, called START, seems to be for those who have already received a round of therapy. Indeed, their website states, “candidates for the START program include those who suffered a stroke at least six months ago and are seeking a fuller recovery.”

The article about the program notes that patients often find themselves in a gray area after some therapy, wondering what to do next when they haven’t fully recovered. Sound familiar?

Closer to home, a woman who read my blog post about my father’s stroke contacted me. She is a journalist researching and writing a book about stroke recovery and the insight families have gained in the process. She has interviewed stroke survivors and doctors across the country.

She also happens to have spoken with a neurologist and occupational therapist at USC Keck School of Medicine for her book, including my father’s occupational therapist there.

With her assistance we discovered the stroke clinic at USC. The neurologist there gave an honest assessment of what he thought was still possible for my father after asking about our recovery goals and my father’s medical history.

The biggest relief was that the staff at USC want to help him and will advocate on his behalf. The neurologist recommended my father start physical therapy again. Hearing this was validation of my efforts and acknowledgment that I am not crazy or unrealistically optimistic.

I was nervous about going to the stroke clinic. What if the first neurologist was right? What if there was nothing else we could do? I was worried I had failed, and that we had now reached the end of the line. That the one-year anniversary of his stroke signaled we had the lost the fight.

Two weeks ago, my father’s occupational therapist saw my father’s left hand move. This is his weak side, where there has not been any movement since the stroke. There have been a few times now that we’ve wondered if his movement was intentional but it didn’t seem involuntary. I wondered if something on that side of his body is awakening.

And on Wednesday (April 13), my father was able to move him his left arm. Again, this is the side of his body that was damaged by the stroke. There was no doubt he dictated the movement.

Initially, I didn’t realize he was moving his arm. I thought it was his therapist. But then she asked that he do it again, and he did. I saw his right arm flex and his right leg jut out as he watched his left arm. He was clearly using tremendous effort to will his awakening limb to life.

I congratulated him. This arm has not moved in a year. Since the morning of March 23, 2015. And now, he had managed to send the message to his arm to move and the nerves and muscles responded. I told him that was a great accomplishment and shook his hand. He nodded.

I congratulated him. This arm has not moved in a year. Since the morning of March 23, 2015. And now, he had managed to send the message to his arm to move and the nerves and muscles responded. I told him that was a great accomplishment and shook his hand. He nodded.

His therapists ask him if he is willing to push harder the following week, and he shakes their hand in agreement. He is asked if he understands that there may be some unpleasantness in this process and whether he can push through it. He nods. I see his effort to swallow and talk. He is a willing participant in arm and hand exercises while we wait for a doctor or transportation. He nods when asked if he wants to continue his therapy at USC. And that is all I need to know.

He Talks, Without Words

After my father’s stroke in March, he was rendered speechless.

But he can, and often, looks away, rolls his eyes, reaches for my hand or waves his hand to dismiss me. Early on he learned to shake his head for no, or nod for yes.

He sometimes mouths words to me without sound. A handful of times there has been sound. Like the day he said, “hao,” or good in Mandarin, in a low, raspy voice.

He sometimes mouths words to me without sound. A handful of times there has been sound. Like the day he said, “hao,” or good in Mandarin, in a low, raspy voice.

Last month he expressed frustration, more so than usual, and I suspect it is one of the main or many reasons he pulled out his Gastric feeding tube, or G-tube — twice — in two weeks.

When I visited him at he hospital he was angry and agitated — his eyes were large, his stare more like a glare. He took short, hurried breaths.

All he needed was words — angry words.

But even without them, I understood he was not happy.

At one point at the hospital he grabbed my arm and yanked me toward him, mouthing and attempting words, pointing repeatedly to the board on the wall in front of him. All I heard were hissing noises. I could not read his lips.

I asked him a series of questions, and asked that he point to the word “yes” or “no” that I wrote on a piece of paper.

He had already shared during occupational therapy that he felt the staff at the skilled nursing facility did not respect him. Our family is quite aware of how aware he is of his surroundings, and while he cannot speak, he will certainly let you know if he is willing to engage with you.

I digress.

His answers were:

Yes, he would like to continue his therapy at USC Keck School of Medicine. (Since December, my father has attended outpatient rehab for speech and occupational therapy.)

No, he does not want to stay at the skilled nursing facility.

So the hunt is on for private insurance as his secondary form of health coverage.

The day after he returned to the skilled nursing facility, I visited him and explained what happened. I stressed that I would continue to look for a new place for him, where he was comfortable and felt respected.

He is now working on non-verbal ways of expressing himself in occupational and speech therapy.

At occupational therapy, my father was introduced to a communication board with basic emotions and expressions. He was able to point to indicate he was sad, that he preferred to watch his news on TV over reading a newspaper (though he still enjoys flipping through the paper) and that he was sleepy.

My father also hit a beach ball back to his therapist, and the next game involved grabbing a bean bag and then placing it in a basket. In addition to hand-eye coordination and having him stretch out his arm to grab the bean bag from the therapist’s hand, his brain is tasked with informing his muscles of when to let go of the bean bag.

Apparently the timing and physical actions required for muscles to release something are more complicated than the process for grabbing something.

At the end of occupational therapy, he was asked how he was feeling.

He pointed to “happy” on the communication board.

In speech therapy, in addition to learning to swallow again, he has been using a stylus to point to words or pictures, or a combination of the two, on a special laptop that we are fortunate to have on loan.

Recently, his speech therapist guided him to a section about feelings, both positive and negative. I stepped back to allow him and his therapist some privacy. This was also the week after his most recent hospital stay, AKA G-tube episode no.2, so I felt he might still have something on his mind.

When she asked about positive feelings, his hand stopped moving. It had been hovering over the different icons on the screen, but now he rested it next to the laptop. She asked that he look at the positive emotions, and identify and point to the “happy” emotion. He did as she asked. His hand again rested next to the laptop, indicating he was done with this section.

She then asked him to look at the negative emotions.

His eyes scanned the screen.

There were plenty of options to choose from, and the therapist read them out loud to him.

Then she asked that he choose the emotions that he was feeling.

Most of his selections did not surprise me: angry, mean, anxious.

But his selection of “guilty” was surprising.

He stared at the screen for some time, and continued to move it up and down to see all of the emotions.

I thought of his possible reasons for feeling guilty.

And then it became obvious. He was having to be taken care of. Literally moved from one place to another. He does little on his own. His mind seems to be functioning, although sometimes it is slower.

Even before the stroke there were times he would tell me he could not remember some things. He walked without a cane or walker before his stroke, but he sometimes walked with a limp. It was likely the result of insufficient therapy after a fall a few years ago.

I thought of his possible reasons for feeling guilty.

And then it became obvious. He was having to be taken care of. Literally moved from one place to another. He does little on his own.

I also wondered if his guilt is tied to regret. Does he feel guilty for any or some of the things he’s said or done to us? Does he wonder if things could have been different? He was often an angry man, enforcing his will easily because few dared to disagree with him. Eventually I did, and it resulted in a cavernous divide between us.

He certainly has a lot of time to think. I often wonder if he would dare to share the thoughts that I think have crossed his mind.

Language is such a significant part of how we communicate — yes, non-verbal cues such as body language and facial expressions are important, but what we say carries so much weight.

When someone cannot always express themselves, you learn to find other ways to reach them. At least I do. My Mandarin vocabulary continues to expand. I learned Spanish, my Mexican mother’s native tongue, but not Mandarin. I feel this disadvantage more now that he cannot speak.

Culture and language came up recently when I planned a small but belated Chinese New Year celebration at the nursing facility with him. It is easier for him to understand his native Mandarin than English, and I find myself translating words and phrases to Mandarin quite often.

I know little about the new year traditions because my father didn’t teach them to us. My knowledge of the holiday was limited to lunch or dinner in Chinatown when I was young. From our table, I watched the men outside the restaurant holding large paper dragons, making them snake up and down and dance, and making me curl away in fright.

But I do not attempt to hold him accountable for the past anymore. I am pleased to see that he makes progress, and happy to celebrate those accomplishments with him. I do hope that he will speak again, at least say a few words at a time. But I stay focused on the now, and what he can accomplish today.

And as long as that list continues to grow, then we are both heading in the right direction.

Do You Want to Talk?

Even before his stroke the words to apologize and explain often eluded him. And now, sitting in a bed, completely dependant on someone else, without the ability to say a word, my once fiercely independent, loud and commanding father has no control of his world.

My sister was in town for the holidays, which meant she was going to visit our father. She had not seen my father since he was hospitalized after his stroke in March.

She wanted someone to go with her. I told her my brothers, who were staying at my mom’s house for Christmas, would be happy to take her.

But she said she wanted someone with experience. A “veteran,” she said. And that veteran was me.

I knew and she knew it would be an emotional visit with my father.

Ours is a complicated relationship, and as he learns to swallow, talk and move his appendages all over again, his triumphs and difficulties seem to carry even more meaning.

We arrived at the nursing facility, and she walked with me from the back of the facility toward his room. His room is near the front of the facility, and his bed is near a window that faces a main street. It’s not a bad view. The passing cars can serve as a distraction and have a rhythm to their flow. There are sufficient trees to add some color and softness to the mix of concrete and asphalt.

I loudly announced my presence, but he seems to hear or sense when someone walks in the room because he had already turned his head to look in my direction as my words made their way out of my mouth.

He saw that my sister was somewhat behind me as I told him he had another guest.

I turn to look at her and move aside so she can have access to his bedside.

My father began to sob as she approached him.

She asked him how he was doing, and I heard her voice crack before I saw the tears well up in her eyes. She hugged him because my sister is a hugger.

She asked him how he was doing, and I heard her voice crack before I saw the tears well up in her eyes. She hugged him because my sister is a hugger.

There was silence.

I wondered what he would say to her if he could speak. Or if he would say anything at all. We were never good at talking about the obvious. And when you add hurt and a complicated past, it gets…complicated.

My sister wiped her tears away, and I told my father it was OK.

I transitioned into my usual routine of sharing the latest family news, current events, etc.

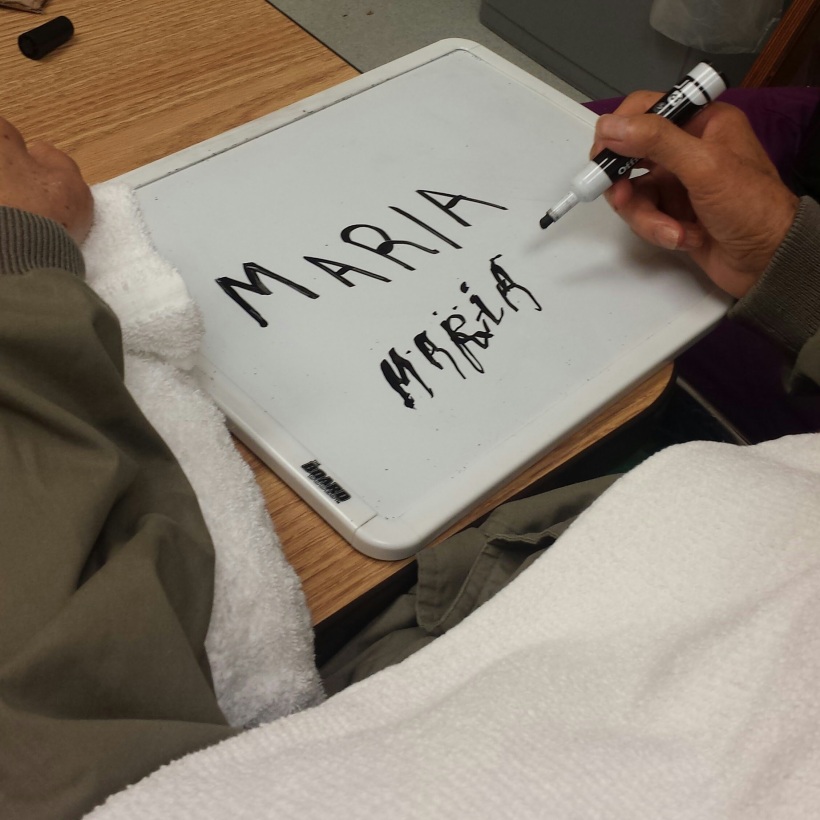

We practiced writing on his whiteboard, but it looked like he was either trying to write his full name in cursive or he was attempting to write Chinese characters. It’s possible he was too emotional to write and could not concentrate. So we practiced just writing the letter “F”, for Frank.

My sister stepped out of the room for a few minutes.

When she returned, my father and I were still working with the board.

I switched gears and asked if he’d like to see some photos.

He nodded, and we started going through the photos on my phone.

I checked the time and my sister and I told him we had to make a mad dash across town to LAX so she could catch a flight home.

Since their emotional greeting he had not looked at her, and the mix of joy, embarrassment and possibly guilt still hung in the air.

My sister asked me if I noticed, and of course I noticed, but I was not surprised.

Since their emotional greeting he had not looked at her, and the mix of joy, embarassment and possibly guilt still hung in the air… Even before his stroke the words to apologize and explain often eluded him. And now, sitting in a bed, completely dependant on someone else, without the ability to say a word, my once fiercely independent, loud and commanding father has no control of his world.

Even before his stroke the words to apologize and explain often eluded him. And now, sitting in a bed, completely dependant on someone else, without the ability to say a word, my once fiercely independent, loud and commanding father has no control of his world.

He has a Chinese calendar in his room now, and I showed him on the calendar that he had a week off before he begins his work with the USC therapists again.

The occupational therapist worked with him on straightening and extending his fingers, and she soon presented him with an opportunity to practice writing.

He immediately began to write his name when the therapist handed him the marker.

The letters appeared shaky, but it was clear enough to make out his name.

She asked if he could write my name, and then she wrote my name on the dry erase board and asked him if he could trace over it.

He looked at the board, studied the words and then wrote my name.

I was sitting across the table from my father and the therapist, fiddling with my phone, when I heard the therapist’s voice rise in delight. She congratulated him on writing my name so clearly. I looked up. I too was delighted. I walked over and snapped a quick photo and congratulated him.

My father started to shake and his face became red. His emotional reaction to writing my name made me emotional as well.

Especially because the word was written so clearly.

He continues to make progress with his ability to swallow, and it is not uncommon for him to be able to swallow after he coughs. It is also a littler easier for him to swallow, and he is now swallowing without the assistance of the VitalStim therapy (electrical stimulation for his throat muscles).

The speech therapist also began having him practice talking – mouthing responses in addition to nodding or shaking his head.

I often wonder if he wants to talk. Perhaps it’s easier for him not to since it allows him to continue avoiding the past. Perhaps he does not want to discuss what is happening to his body and his mind.

We came to an agreement that once he began eating, I would take him out to dumplings. I asked him one day if he missed eating and the taste of different foods. If he missed Chinese food. He laughed. Which I think means yes… I have not mustered the courage to ask if we wants to talk.

We came to an agreement that once he began eating, I would take him out for dumplings. I asked him one day if he missed eating and the taste of different foods. If he missed Chinese food. He laughed. Which I think means yes.

I have not mustered the courage to ask if he wants to talk.

A few times in therapy we leaned in to hear him utter a very low, hoarse response.

Of greater importance is the opening and moving of the mouth, tongue and all the related muscles, the therapist said. Sounds, of course, are great, but she wants him to engage more.

Back at the skilled nursing facility, I practiced what he had done in speech therapy, encouraging my father to “talk” and mouth his responses.

Before leaving, I mentioned when our next appointment was, and asked if that was OK, or “good” with him, in Chinese.

“Hao?” I said.

He nodded and opened his mouth.

“Hao,” he responded, in a raspy, Darth Vader-like voice.

“I could hear that!” I said. “That’s good – hun hao (very good).”

He began to shake and cry.

These are small steps, but steps nonetheless, I told him.

“Hun hao,” I repeated, with tears in my eyes.

Very good indeed.

What a Wednesday – Rehab at USC

So it finally happened.

My father’s evaluations for speech and occupational therapy took place on Dec. 2 at USC’s Keck School of Medicine. My father will be visiting the outpatient rehabilitation center twice a week now.

Since his stroke in March he is unable to speak, although he understands everything going on around him. He cannot move the left side of his body. His right arm and hand are pretty active, but he lacks sufficient hand control to write.

He eats through a tube that connects to his stomach and is not able to swallow consistently. It led to him aspirating and catching pneumonia, and a 10-day hospital stay.

But that led to the discovery of the existence of VitalStim therapy, essentially electrical stimulation on his throat to help the muscles move and contract when swallowing.

Since October, I have pushed the skilled nursing facility to help me get my father to USC’s outpatient rehab center, where VitalStim is offered with speech therapy. The nursing facility does not offer VitalStim.

It only took four weeks for the nursing facility to get all the paperwork to USC.

Getting three pieces of paper to my father’s doctor’s office is apparently a team effort. It involved the social worker, billing manager, marketing manager, me and my sibling, and USC saying something similar to, “I told you, I haven’t received it yet.”

Then, getting the doctor’s signature on those three pieces of paper and making sure they were faxed to USC was the equivalent of walking uphill in a snowstorm, backwards. And barefoot. With your eyes sealed shut.

Then, getting the doctor’s signature on those three pieces of paper and making sure they were faxed to USC was the equivalent of walking uphill in a snowstorm, backwards. And barefoot. With your eyes sealed shut.

Yes, we’ve considered moving him to another skilled nursing facility.

We wonder how that might affect his care at USC and if the transportation to USC would be covered if the new nursing facility is further away. It currently takes less than 20 minutes to get to USC from the nursing facility. When the driver doesn’t get lost, that is.

I think the visits to USC will be a welcome break from the monotony of the nursing facility. It will also allow my father to see what is happening in the outside world.

Since his stroke in March, he has been confined to a bed in a hospital room. Now, at the nursing facility, he alternates from his bed to a wheelchair (with assistance), and watches movies in the main activity room.

A few times a week he is pushed down the long hall to the therapy room, on the opposite side of the facility from his room. There the staff stretches his limbs and has him participate in strengthening exercises.

The Wednesday morning we were scheduled for the evaluations was a chilly one, which in Los Angeles means it was hovering in the upper 40s. But the day began to warm up by the time we arrived at USC.

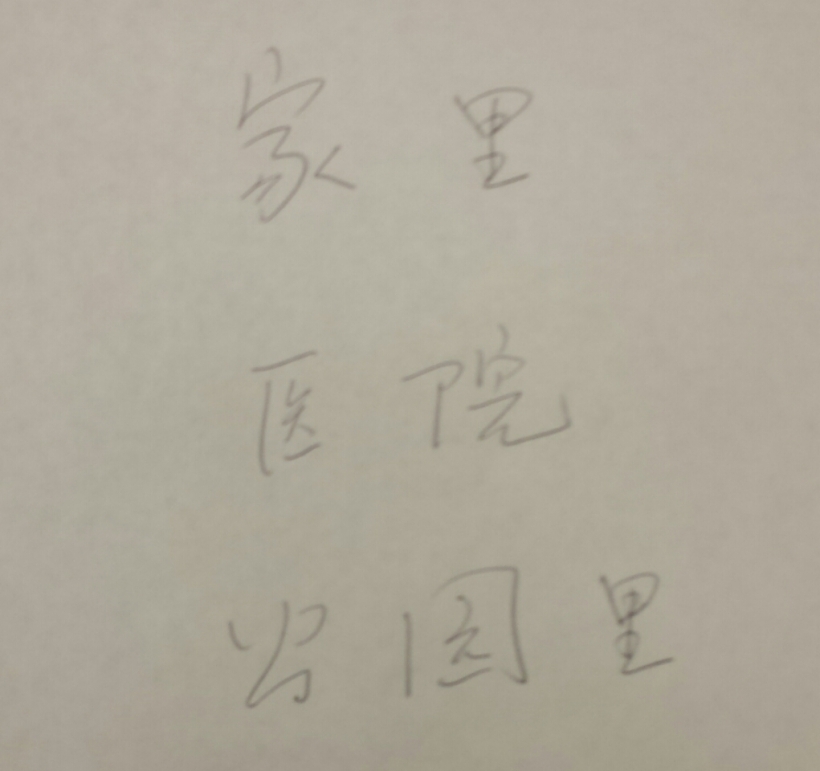

The occupational therapist who will now be working with him is an older woman with curly black hair and glasses, who spoke to my father in Mandarin.

I am not fluent in Mandarin and had to interrupt a few times to ask what was going on, especially when I saw the surprised look on her face each time he’d respond.

She asked my father in Mandarin where he was, and held up a piece of paper with three rows of Chinese characters.

The words were house, hospital, park.

He looked at the piece of paper, and quickly pointed to the middle row of characters for “hospital.”

The therapist then wrote down several rows of letters in English. She asked my father to spell out his name.

He quickly began to point to each of the letters in his name, Frank, sometimes before she asked.

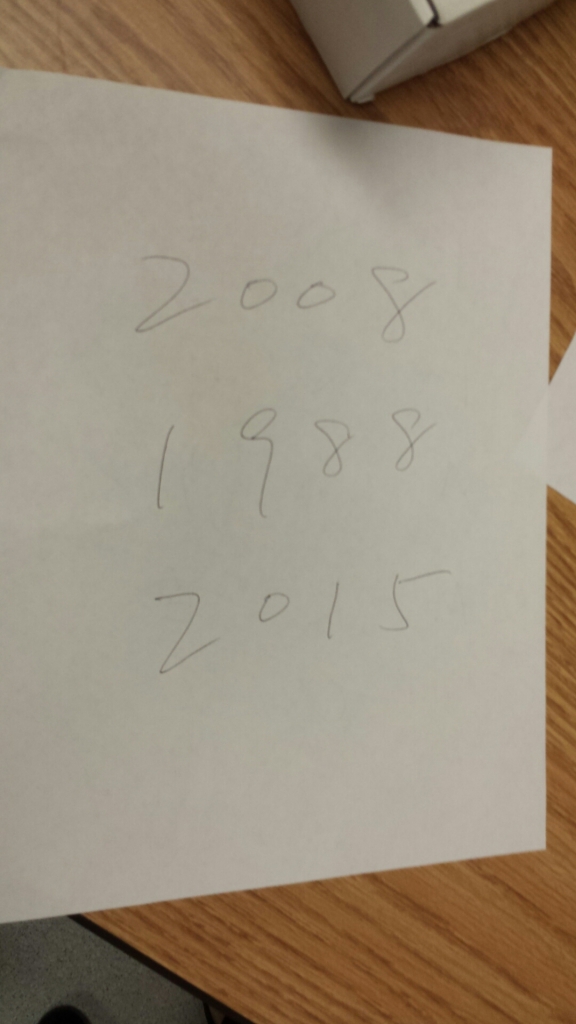

Another part of her evaluation included three years: 1998, 2008 and 2015. She asked him to tell her what year it was.

He scanned the sheet of paper, and picked the correct year, without hesitation.

It is my custom when I see him to tell him the day and date, and now I show him the calendar on my phone so he can see his appointments.

When she asked if the nursing facility staff respected him and treated him like he knew what was happening, he began to sob and shook his head no.

She became emotional as well.

It became evident through other questions that he would like to read, and because of his interest in writing, the therapist has recommended a dry erase board for him to practice writing.

I asked if he would like to read Chinese newspapers, and he immediately nodded.

When I came by to accompany him to his second speech therapy appointment, I told him I had something for him.

He quickly turned to look at me, saw that I was digging something out of a bag, and his eyes seem to light up when he saw that I was taking out newspapers.

I laid them out in his lap, since he was sitting in his wheelchair, and positioned them so he could see each one.

One of the papers was a recommendation from a cousin as his father reads that paper, and I shared this with my father.

He nodded.

I asked if he liked these newspapers.

He nodded.

I said I’d make sure we got him a subscription so he could read them in his room.

He nodded again.

Both papers had the high level of Beijing smog as the main story on the front page, and my father’s eyes darted to the photo of people with surgical masks amid a gray background.

I enjoyed seeing him with the newspaper. It reminded me of the countless times I watched him go through the paper when I was a child. It is likely the reason I gravitated toward journalism. I saw the effect it had on him — he scoffed or laughed, depending on what he was reading.

My grandfather and my father owned their own printing businesses, so it is not surprising he was, and apparently remains, such an avid reader of the news.

The speech therapist has seen my father three times now, and each time, there is some small step forward. I’ve told my father several times that each improvement is significant.

His speech therapist noted the improvements as well. She keeps a tally of the number of swallows, and he has gone from one to five. The next goal is seven swallows.

When I asked my father last week if he wanted to return to USC, he nodded.

You’re welcome USC, for the free advertising. It’s a been a pleasure thus far.